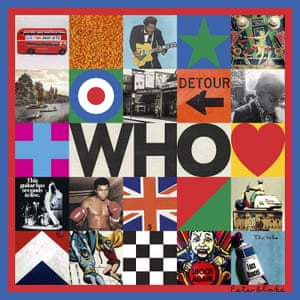

(Polydor)

Despite their precarious relationship, Daltrey and Townshend return for their first album in 13 years, snarling at the Grenfell disaster and hoping for world peace

Thu 28 Nov 2019 07.00 ESTLast modified on Thu 28 Nov 2019 13.34 EST

Shares64Comments334

The first words you hear on the Who’s 12th studio album are Roger Daltrey, telling the band’s audience to get stuffed. “I don’t care,” the band’s 75-year-old frontman sings, “I know you’re going to hate this song.” There follows four and half minutes of agonising over whether there’s any point in making a new Who album at all – “this sound that we share has already been played” – before songwriter Townshend signs off on All This Music Must Fade with a muttered “who gives a fuck?”

This is obviously not the way heritage rock artists essaying their first album in 13 years are meant to carry on. Then again, it feels, well, very Who. No member of the rock aristocracy has ever seemed as troubled by the very notion of being a rock star as Pete Townshend. The Who weren’t even supposed to be a band, he said in 2006. As far as Townshend was concerned, they were a kind of art school project, complete with a thesis he’d written under the influence of Gustav Metzger’s concept of auto-destructive art, announcing that, as soon as they got famous, they were going to split up. Or worse: at one point, he suggested the band douse themselves in petrol and set fire to themselves on stage.Advertisement

In truth, Townshend ruined his own plan by being such an innovative songwriter and performer that giving up no longer seemed like an option. Instead, he settled for metaphorically thrashing about, seemingly in the throes of a perpetual existential crisis, writing songs that were, as writer Jon Savage put it, “at war”: with the older generation, with the class system, with accepted notions of gender, with the commodification of pop and, frequently, with the Who and their audience. Townshend was big on sending out peevish signals that music was not what it could be. Amid the innovations of 1966, he protested that pop’s innocence had been tragically lost. In 1972, he worked on an unreleased projected called Rock Is Dead. By the time punk arrived, he was declaring himself old and irrelevant: “Am I doing it all again? … We’re chewing a bone.” He was 32.

Forty years on, with half of the Who deceased and the relationship of its two surviving members in a precarious state – Who was recorded without Townshend or Daltrey actually meeting – Townshend seems more troubled than ever. Who certainly does some of the things that artists of their vintage are supposed to do, including make knowing references to their most beloved work. The fantastic Detour has a definite air of Magic Bus, as well as a titular nod to the name that the nascent Who plied their trade under in the early 60s. A Baba O’Riley-ish synth flutters around Street Song; an echo of Substitute’s intro haunts the acoustic guitar of I Don’t Wanna Get Wise.

But the most Who-esque thing about it might be the way its songs repeatedly pick at questions of the Who’s own relevance. I Don’t Wanna Get Wise views a rock career as one of inevitable decline – from “snotty young kids” to “over-full, always sated, puffed-up and elated” – while Hero Ground Zero and Rockin’ in Rage both pitch fears of superannuation against the continued desire to create: “I’m too old to fight … I don’t have a right to join the parade,” suggests the latter, before adding: “you know you must write, you know you must rage.”

If not everything here works – there’s nothing wrong with the political sentiment of Ball and Chain, it just feels a little lumbering and clumsy – there’s something exciting about hearing Townshend vacillating between declaring himself spent and readying himself for another charge. Inspired by the Grenfell disaster, Street Song carries a distinct hint of Won’t Get Fooled Again’s furious snarl; Beads on One String rather sweetly sticks fast to a hippy-ish notion of universal brotherhood and the potential for world peace. Moreover, the changing mood fits Daltrey’s vocals perfectly: gruffer and more weathered than it once was, his voice imbues the lyrics with a sense of hard-won experience, alternately weary and fraught.

Nor is Who afraid of assaulting its audience’s preconceptions. You get the feeling Townshend knows precisely who’s going to buy a new Who album in 2019, largely because he frequently seems to be having a high old time doing precisely the opposite of what they might expect. There are bursts of Auto-Tuned vocals. The sonic nods to “classic” Who sit alongside tracks that do things the “classic” Who would never have countenanced. I’ll Be Back is a lovely, Townshend-sung, harmonica-decorated bit of acoustic MOR that ruminates on dignity and reincarnation, while the folky stomp of Break the News, written by Townshend’s brother Simon, hymns the pleasures of old age, among them “watching movies in our dressing gowns”, which frankly seems like straight-up trolling of the kind of person who feels obliged to bring up My Generation’s thoughts about the relative merits of dying and ageing, whenever the Who’s name is mentioned.

Of course, half of the Who did get old, which means there’s a strong chance this might be their last album. If it is, then they’re going out the way they came in: as cussed and awkward and troubled as ever.